Elvis and Nixon, Reagan and Jacko, Jagger and Blair: When pop stars and politicians collide

Elvis wanted an FBI badge from Nixon. Jacko fought drink-driving with Reagan. Jagger got lovebombed by Blair. Are these the strangest back-room deals in politics?

Craig Brown Sunday 19 June 2016

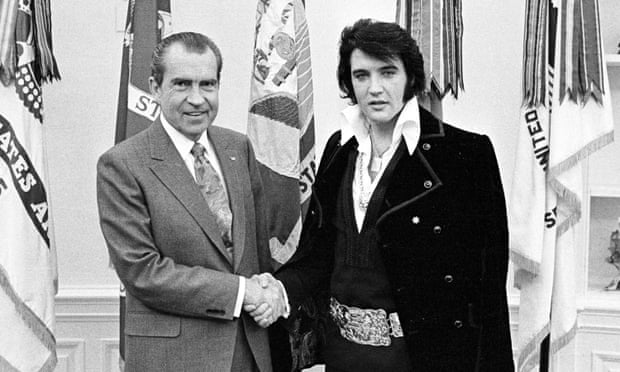

The famous 1970 meeting between Elvis Presley and President Richard Nixon was never going to be easy. At 6.30am, Elvis had dropped off a six-page letter at the White House, asking for a meeting with the president to tackle the problem of drug abuse among the young. He wished, he said, to counter the influence of “the drug culture, the hippie elements, the SDS, Black Panthers, etc”. Above all, he wanted to be made a “Federal Agent at Large”, and be awarded the badge to go with it. Appropriately enough, his paranoia about drugs was exacerbated by the quantity of drugs he had consumed.

Elvis got his badge

His letter triggered a panicky exchange of memos between different presidential aides. “If the president wants to meet with some bright young people outside of the government, Presley might be a perfect one to start with,” read one, against which HR Haldeman, the White House chief of staff, added, “You must be kidding”, before initialling the box marked “Approve”.

The half-hour meeting went pretty well, all things considered, though at one point Elvis went off on a rant against the Beatles, leaving Nixon unsure how to react. “The Beatles, I think, are kind of anti-American,” said Elvis. “They came over here. Made a lot of money. And then went back to England. And they said some anti-American stuff when they got back.”

The White House aide Egil Krogh, who transcribed the conversation, couldn’t work out what Elvis was on about. “From the look of surprise on the president’s face when Elvis said this, I was convinced the president didn’t know what he was talking about either.”

But the odd couple arrived at an accommodation: the pop star got his badge, and the politician was photographed with the most illustrious representative of the young, or young-ish (Elvis was 35). For some reason Elvis & Nixon, the new film about their meeting, fails to include their most telling exchange. Towards the end of the meeting, Elvis hugged Nixon to his chest. This least touchy-feely of presidents somehow managed to extricate himself before taking a step back and looking at the pop star in pancake make-up, brass-buttoned Edwardian jacket, purple velvet tunic with matching trousers, and vast gold belt. “You dress kind of strange, don’t you?” he remarked.

“You have your show and I have mine,” replied Elvis, in what was in many ways the perfect summary of the clear divide between politician and pop star. Yet it had no influence: over the following 46 years, the divide has grown almost totally obscure, the average pop star growing older, grander and more statesmanlike, the average politician younger, more awestruck and deferential. In the old days, a president or prime minister would have shown no more interest in hobnobbing with a pop star than with a window-cleaner. But as the 1950s gave way to the 60s, pop stars had grown more prominent, and politicians had started dancing to their tune.

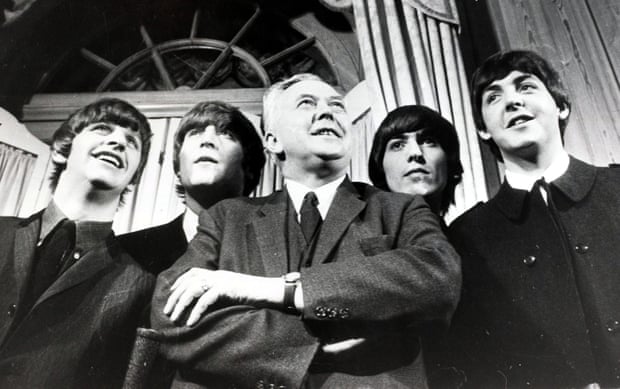

In Britain, meanwhile, Harold Wilson was quick to recognise the importance of the Beatles. In March 1964, as leader of the opposition, he presented them with their “personality of the year” awards at a Variety Club lunch. Watching footage of the event, it is clear which way the deference is flowing: while the Beatles are relaxed and joshing, Wilson seems tense and genuflective. Accepting their awards, Paul says: “You should have given one to good old Mr Wilson!” while John says: “I’d just like to say thanks for the Purple Heart.” “Silver! Silver!” chips in Ringo, in a jokey stage-whisper. Wilson forces a chuckle. The following year, Wilson engineered the Beatles’ MBEs.

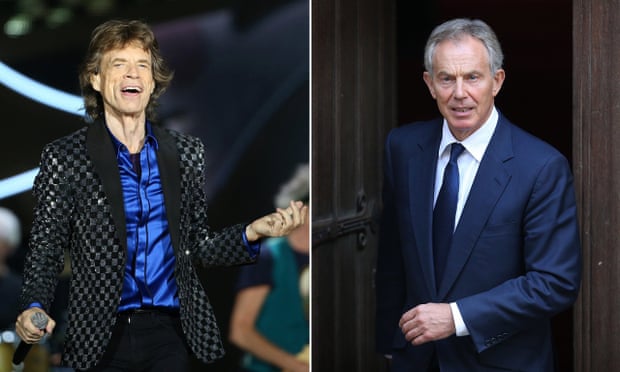

By the second half of the 60s, pop stars were growing more political, sometimes even going so far as to rhyme “solution” with “revolution”. In the spring of 1967, the American poet Allen Ginsberg arranged a meeting between Mick Jagger and the maverick Labour MP Tom Driberg. Britain was on the brink of revolution, Driberg told Jagger, “And the Labour party is where a young man should be when it happens.” Driberg later admitted his surprise at hearing himself say this, as he hadn’t believed a word of it. “But one begins to share that revolutionary hope when one is in the company of someone like Mick.”

Jagger was clearly flattered, but expressed a fear that, if he agreed to become a Labour MP, “I wouldn’t want to have to give any of that up to sit behind a desk … I mean, I don’t exactly see myself scrutinising the Water Works Bill inch by inch, if you know what I mean.” Driberg did his best to reassure him. “Dear boy, we wouldn’t expect you to attend to the day-to-day ephemera of the house. Not at all. We see you more as a figurehead.”

As their meeting went on, Driberg’s eyes began drifting downwards, finally coming to rest on Jagger’s crotch. “Oh my, Mick, WHAT a big basket you have!” he gasped. Jagger blushed, and even Ginsberg was a little shocked, but the conversation soon managed to find its way back to politics. Years later, Marianne Faithfull wrote that Driberg “could see exactly what Mick wanted, which was a form of respectability”.

Ah, respectability! It sometimes seems as though no pop star, however offbeat or rebellious, is immune to its allure. In a bizarre replay of Presley’s visit, President Ronald Reagan welcomed Michael Jackson to the White House in 1984. Asked to donate his song Beat It to a government anti-drink-driving campaign, the beady Jackson had agreed, but only on condition the president presented him with an award for his work against drink and drugs at a special White House ceremony. Documents recently released under the Freedom of Information Act show that the FBI simultaneously agreed to drop an investigation into claims that Jackson was abusing two Mexican children, so as not to embarrass the president.

The president and Mrs Reagan stood on a special platform on the South Lawn to greet Jackson, who wore a military jacket with sequins, plus floppy gold epaulettes and a gold sash, a single white glove with rhinestones, large dark glasses and full stage make-up. The president then commended Jackson as “proof of what a young person can accomplish free of drink or drug abuse”. Years later, Jackson’s autopsy revealed traces of lidocaine, diazepam, nordiazepam, lorezepam, midazolam, propofol and ephedrine.

By the end of the 1980s, it had become de rigueur for politicians and pop stars to hobnob, and even to perform together. Neil Kinnock appeared on Top of the Pops, acting the part of Tracey Ullman’s My Guy in a video; and in 1992 Mick Hucknall of Simply Red broadcast his commitment to socialism to a Labour rally, via a satellite link-up from the south of France.

The balance had switched: it was now the pop star who conferred respectability on the politician rather than vice versa. The new generation of political leaders were the children of Elvis and the Beatles: they looked up to their older pop idols. When President Bill Clinton and Tony Blair met Chuck Berry, it was, reported Blair, “a mutual case of ‘Wow!’ Never mind about meeting world leaders, this was a REAL superstar.” Can you imagine Churchill and Roosevelt undergoing a mutual case of “Wow!” after shaking hands with George Formby?

Blair had, of course, been lead singer with the group Ugly Rumours, wearing purple loon pants and whooping “Let’s go, honeys!” before launching into a cover version of Honky Tonk Women. Of all the party leaders, he was to prove the keenest, gushiest autograph-hunter, almost as though somewhere in the back of his mind he was still awaiting the call from the producer of Top of the Pops. In his memoirs, Peter Mandelson recalls how, at one dinner party, Tony Blair “summoned up his courage” to go up to Mick Jagger and tell him: “I just want to say how much you’ve always meant to me.”

But, then again, even the most strait-laced Conservative leaders were once pop-pickers: in his biography of Michael Howard, Michael Crick revealed that Howard sported an Elvis quiff in his youth. “He wanted to BE Elvis Presley,” said his cousin Renee. “He used to sit in the bath shrinking his jeans.”

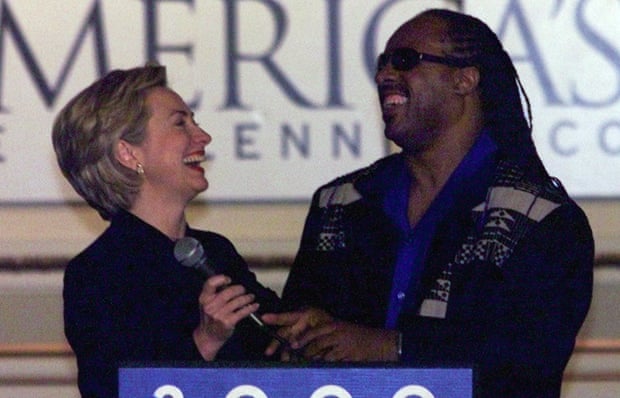

On both sides of the Atlantic, politicians would now offer obeisance to pop stars. Sometimes, they even sought a form of absolution from them. In her memoirs, Hillary Clinton writes of taking a phonecall, at the height of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, from Stevie Wonder, who “had attended the state dinner for another of his fans, Czech president Vaclav Havel, the night before”. Wonder asked her if he could come over and play a song he had composed for her about the power of forgiveness. “As he played, I kept moving my chair closer to the piano until I was sitting right next to him. When Stevie finished, tears filled my eyes…”

Four years later, Bono dropped in on the White House to have a word with President George W Bush. “He brought me a thoughtful gift, an old Irish Bible,” Bush recalls in his memoirs. The lessons were all one-way: within minutes, Bono was quoting verses from the New Testament at a reverential Bush. The two men then rode in the president’s limo to a conference at the Inter-American Development Bank. “Bono participated in the event and praised our policy … Laura, Barbara, Jenna, and I consider him a friend.”

Three years later, in preparations leading up to the G8 conference, the chancellor, Gordon Brown, was in discussion with Bono and Sir Bob Geldof. Before long, anyone who had ever topped the charts – Chris Martin, Annie Lennox, Madonna, Sting – was allowed to deliver a lecture on poverty to politicians whose salary amounted to about half as much as one of their junior hairstylists.

Pop stars are the new grandees. They enjoy the kind of status, wealth and respect once accorded to Lord Curzon, issuing eagerly awaited proclamations on world affairs from the comfort of their stately homes, their careers crowned with gongs for long service.

There has been the occasional hiccup, of course. At the Brit awards in 1998, Danbert Nobacon of the rock group Chumbawamba spotted a bucket of ice cold water on one table and John Prescott on another, and was overcome by the understandable urge to pour the one over the other. “Mr Prescott thinks it is utterly contemptible that his wife and other womenfolk should have been subjected to such terrifying behaviour,” said a spokesman from his private office, and, for that brief moment, the natural order of things was restored.

- Elvis & Nixon is released in the UK on 24 June; and is on limited release in the US

Source TheGuardian