Isle or Rhum

On Rum, magma domed up along the Main Ring Fault, raising the earth’s surface by some 2,000 metres. After the release of the pressure of the magma the huge dome collapsed forming a massive caldera over the southern half of Rum. The magma pushed up Lewisian Gneiss as it rose from beneath the Torridonian sandstone. This gneiss is some of the oldest rock in the world at nearly 3 billion years old. The caldera was slowly filled in by further eruptions and collapses of the surrounding walls, forming the layered structures of Hallival and Askival. When the eruptions eventually stopped the Rum volcano was subjected to erosion and repeated periods of glaciation, sculpting the island into its current shape.

The Geology of Skye

The Geology of Skye, in Scotland, is highly variable and the island’s landscape reflects changes in the underlying nature of the rocks. A wide range of rock types are exposed on the island, sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous, ranging in age from the Archaean through to the Quaternary.

Contents

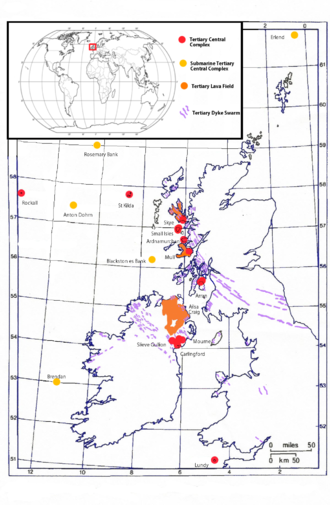

The North Atlantic Igneous Province

(NAIP) is a large igneous province in the North Atlantic, centered on Iceland. In the Paleogene, the province formed the Thulean Plateau, a large basaltic lava plain,[1] which extended over at least 1.3×106 km2 in area and 6.6×106 km3 in volume.[2] The plateau was broken up during the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean leaving remnants existing in Northern Ireland, bits of northwestern Scotland, the Faroe Islands, bits of northwestern Iceland, eastern Greenland and western Norway and many of the islands located in the north eastern portion of the North Atlantic Ocean.[3][4] The igneous province is the origin of the Giant’s Causeway and Fingal’s Cave. The province is also known as Brito-Arctic province (also known as the North Atlantic Tertiary Volcanic Province) and the portions of the province in the British Isles is also called the British Tertiary Volcanic Province or British Tertiary Igneous Province.

Contents

Contents

The Cuillin is a range of rocky mountains located on the Isle of Skye. The true Cuillin is also known as the Black Cuillin to distinguish it from the Red Cuilin (na Beanntan Dearga, known locally as Red Hills) across Glen Sligachan. The Red Cuilin hills are lower and, being less rocky, have fewer scrambles or climbs.

The highest point of the Cuillin, and of the Isle of Skye, is Sgùrr Alasdair in the Black Cuillin at 992 m (3,255 ft). The Cuillin is one of 40 National Scenic Areas in Scotland.[1]

Munro

(SV = 360° Summit View)

Skye is about 50 miles from north to south, and around 25 miles from west to east at its widest. The coastline is very irregular and indented by sea lochs. In all it is some 400 miles long – and I can’t think of a single mile of those 400 that I would class as dull. The coast is littered with bays, sea arches, stacks, caves, massive cliffs, waterfalls, fossils, tidal islands – a lifetime’s worth of exploration and discovery.

This dramatic coastline surrounds some of the most exceptional and varied scenery to be found anywhere. The main mountain range, the Cuillin, is often said to be the home of the only true mountains in Britain. Certainly there is nowhere in the country to compare with the magnificent, dramatic and challenging peaks and ridges of the Cuillin.

Nearby, the rounded granite lumps of the Red Hills are less savage, but still offer stunning views – both of them, and off them.

In the north-east is the Trotternish Peninsula, with the world famous ridge or escarpment that forms its backbone. The ridge rises to its highest point at the summit of the Storr, above the tortured landslip topography that includes the iconic pinnacle – The Old Man of Storr. The ridge is home also to the Quiraing, another landslip area of pinnacles and gullies, this time below the summit of Meal na Suiramach.

The face of the Quiraing

To summarise simply, there are three main geological regions:

The south-east has some of Britain’s oldest rocks in the form of 3,000 million year old Lewisian Gneiss. These are overlaid by younger (c800million year old) sedimentary rocks, mainly Torridian Sandstone.

The Cuillin is much younger, being the heavily glaciated remains of a solidified volcanic lava reservoir some 60 million years of age. Just south of the Cuillin can be seen limestone in Strath Suardal. This gives rise to the complexes of caves in the area. It is metamorphosed limestone that forms the marble that is still extracted commercially at Torrin.

The Storr reflected in Loch Fada